|

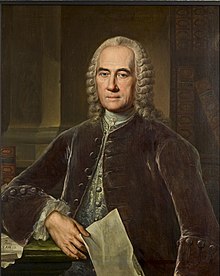

Jacob Theodor Klein

Jacob Theodor Klein (nickname Plinius Gedanensium; 15 August 1685 – 27 February 1759) was a German jurist, historian, botanist, zoologist, mathematician and diplomat in service of Polish King August II the Strong. LifeKlein was born on 15 August 1685 in Königsberg, Duchy of Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia).[1] He studied natural history and history at the University of Königsberg. Between 1706 and 1712, Klein travelled through England, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Dutch Republic in an educational journey, before returning to Königsberg.[2]  He moved to Danzig after the death of his father, where he was elected city secretary in 1713. Between 1714 and 1716 he served as the city's representative, or “resident secretary at court,” (residierender Sekretär) in Dresden and then Warsaw.[3] Klein began his scientific works in 1713 and began publishing his findings by 1722, as a member of the Institute of Sciences in Bologna. Influenced by Johann Philipp Breyne, his works dealt with matters of zoological nomenclature, and he set up his own system of classification of animals, which was based on the number, shape, and position of the limbs. He used his position as secretary to found a botanical garden there (now called Ogród Botaniczny w Oliwie).[1][3] For his work in the natural sciences, Klein had been rewarded with membership of several scientific societies, including the Royal Society in London, the Academy of in St. Petersburg, the Deutsche Gesellschaft in Jena, and the Danzig Research Society.[2][3] One of Klein's daughters, Dorothea Juliane Klein, married physicist Darniel Gralath, who would become mayor of Danzig. Gralath inherited Klein's library, which was praised by Swiss mathematician Jogann Bernoulli.[2] Klein died on 27 February 1759 in Danzig.[4] Botanical garden and "Museum Kleinianum" Using his position as secretary of Danzig and with the help of other scholars, Klein set up a botanical garden in 1718, which was one of, if not the largest of its time.[5][6] The garden was expanded to include live animals, zoological, fossil and amber collections, the shell collection of the mayor of Amsterdam Nicolaus Witsen, as well as a greenhouse which he used for experimentation with exotic plants. The collection became known as the Museum Kleinianum. It was sold to Margrave Friedrich of Brandenburg-Kulmbach in 1740.[2][1] After the Margrave's death in 1763, the collection was donated to the Friedrich-Alexander Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU).[7] It was praised by prominent Swiss mathematician Johann Bernoulli, who visited the museum in 1777 or 1778. Scientific worksSystem of classificationInspired by Johann Phillipp Breyne, Klein developed an interest in science as early as 1713 and began publishing in 1722.[2] He was especially interested in the systematic classification of living organisms, but excluded insects from his classifications.[3] His system was based on external, easily identifiable traits, such as the number, shape and position of limbs. This put his work in opposition with that of Carl von Linné, of whom he was critical,[8] and whose work has since garnered more widespread recognition, though some of Klein's classifications are still in use, for example, in the naming of echinoderms.[9][5] His work on sea urchins was the most prominent source of information on the species at the time.[5] His essay Tentamen Herpetologiae (1755) featured the first mention of the term herpetology - the study of amphibians. However, his system of classification meant that species such as frogs and lizards, which belong to amphibians and reptiles respectively, were not distinguished as belonging to separate classes.[citation needed] Klein was critical of Linnaeus' system of classification, believing only easily recognisable features could be used to classify animals, as Adam had done when naming animals according to the Biblical story of creation.[3] Historiae Piscium Naturalis Klein published Historiae Piscium Naturalis, in Danzig, in five parts from 1740 to 1749. The first part (1740), dedicated to the Royal Society, focused on understanding the auditory capacity of cartilaginous and spinose fishes. According to John Eames (1742), until the publication of the work, it was believed to have been understood that only cetaceous fish were known to have auditory passages, or ear holes, and that the question of whether fish could hear was still not understood. Aristotle claimed, in his "History of Animals," that fishes possessed no evident auditory organs, but believed that nonetheless they must hear.[10] In the Preface, Klein cites the work of Giulio Casare Casseri, who discovered bones in the heads of Pike or Jack fish, which he understood to be their organs of hearing, though he did not discover any manifest external auditory passages. In section of the essay titled De Lapillis, eorumque Numero in Craniis Piscium (roughly translated as “The bones, their number in the skull of Fish”) Klein considers what parts of the head of fish serve as the organ of hearing, and by what passages the sensation of sound is communicated to them. He refers to these bones as Ossicula – little bones – and considers them essential parts of the head, generated with the brain itself. Now known as otoliths, he notes that they scale proportional to the size of the fish, and are most easily discovered in the heads of bony fish. Klein identifies three otoliths to correspond to the Incus, Malleus and Stapes of other animals. The first are the two largest, which he explains are easily found; the other two pairs, he explains, are small, difficult to find, enveloped in distinct fine membranes. Klein also suggested that one could determine the age of fish by analysing the number and thickness of the Laminae and fibres of these bones. Otoliths are now known to acquires a growth ring every day for at least the first six months of its life.[11] Klein inquiries into the nature of the passages by which vibrations produce a sense of hearing. He inspects the head of a Pike fish and observes several holes with bristles which lead to the auditory bones. He later dissected a Sturgeon fish and traced the auditory duct to the membrane in which the three bones are placed. Klein concludes that fishes do indeed have hearing organs and passages, communicated to through slight vibrations, though these passages are not easily demonstrable in many species. He observes that the auditory organs of cetaceans are different from those of cartilaginous and bony fishes. He adds that water does not act as an impediment to hearing, but rather is the “intermedium” by which sound is communicated.[12][13] HonoursKlein had been awarded the membership of several scientific societies, including the Royal Society in London, the St. Petersburg Academy, and the Danzig Research Society.[2] The name of the genus Kleinia was given to the plant family of Compositae (Asteraceae) by Linnaeus in honour of Klein's works.[14][15] He was described as the most important natural philosopher of his century by Professor Johann Daniel Titius.[3] CriticismAlthough well respected by his colleagues,[2] Klein was nonetheless accused by some contemporaries of being unscientific, alleging that he based his beliefs on the hearsay and the claims of ‘credulous’ people. The 1760 edition of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London published a letter by 18th Century botanist and Fellow of the Royal Society, Peter Collinson, criticizing Klein for his belief that swallows (sand martins) are not migratory birds, and instead ‘retire under water’ during winters. Collinson accused Klein's assertion as being “contrary to nature and reason,” and provided observations of Marine officers, such as Sir Charles Wager, to further his claim.[16] List of works

See alsoReferences

|

||||||||