|

Licensing Act 1737

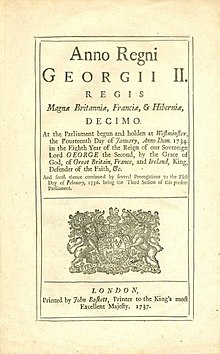

The Licensing Act 1737 (10 Geo. 2. c. 28) or the Theatrical Licensing Act 1737 is a former act of Parliament in the Kingdom of Great Britain, and a pivotal moment in British theatrical history. Its purpose was to control and censor what was being said about the British government through theatre. The act was repealed by the Theatres Act 1843, which was itself replaced by the Theatres Act 1968. The Lord Chamberlain was the official censor and the office of Examiner of Plays was created under the act. The examiner assisted the Lord Chamberlain in the task of censoring all plays from 1737 to 1968. The examiner read all plays which were to be publicly performed, produced a synopsis and recommended them for licence, consulting the Lord Chamberlain in cases of doubt. The act also created a legal distinction between categories of "legitimate theatre" and "illegitimate theatre". ForerunnerThe function of censorship of plays for performance (at least in London) fell to the Master of the Revels by the time of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. The power was used mostly with respect to matters of politics and religion (including blasphemy). It was certainly exercised by Edmund Tylney, who was Master from 1579 to 1610. Tylney and his successor, George Buck, also exercised the power to censor plays for publication.[1][2] The Master of the Revels, who normally reported to the Lord Chamberlain, continued to perform the function until, with the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, stage plays were prohibited.[3] Stage plays did not return to England until the Restoration in 1660.[4] During the creation of the Licensing of 1737, Robert Walpole was the standing Master of the Revels[5]: 4 Purpose of the actLaws regulating theatre in the early 18th century were not strictly enforced.[5]: 13–22 People had free rein to say anything they wanted through theatre, including all their troubles with the government.[5]: 3–5 Free speech in theatre was seen as a threat to the government, facilitating the spread of revolutionary ideas.[5]: xi The act enhanced government control and censorship.[5]: 4–5 Examiner of PlaysIn addition to reading plays and writing Reader's Reports for the Lord Chamberlain the Examiners were expected to visit theatres to ensure their safety and comfort and to see that the Lord Chamberlain's rules were carried out with regard to the licences. They were also required to appear at subpoenas in law cases relating to licensing, and to examine Play Bills.[6] From 1911 Examiners were required to write reports on plays for the Lord Chamberlain.[7] A copy of the play script and Reader's Report were held by the Lord Chamberlain's office and are now held by the British Library in the Lord Chamberlain's Plays collection. In the years 1922–1938 when The Earl of Cromer was the Lord Chamberlain nearly 13,000 plays were licensed, an average of 820 a year; under 200 plays were refused a licence, an average of 12 per year.[6] There were 21 Examiners of Plays between 1738 and 1968.[6][8]

The Examiners had a variety of qualifications and experience for the position. Edward Pigott (1824–1895) was a journalist on the Daily News and had an extensive knowledge of European literature and languages.[9] George Redford (d. 1916), a playwright, resigned his post in 1913 to become the first president of the British Board of Film Censors.[6][10] Ernest Bendall (1846–1924) had been a clerk in the Paymaster-General's Office for 30 years retiring in 1896 to become a journalist and drama critic for several London newspapers.[6][11][12][13] Charles Brookfield was an actor, playwright and journalist.[14] George Street was an essayist, novelist and playwright.[15][16] Henry Game (d. 1966) trained as an artist, was an amateur actor and was known for his knowledge of the theatre.[17] Charles Heriot (d. 1972) was an actor and producer.[6][18] Sir St Vincent Troubridge (1895–1963) was in the military as well as being a theatre historian.[19][20] Ifan Kyrle Fletcher (d. 1969) was a theatre historian and antiquarian bookseller.[21] Timothy Harward studied theatre and literature at university, becoming a theatre journalist for the Irish Times and lecturer at Regent Street Polytechnic.[6] See alsoReferences

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||