|

Mario Andretti

Mario Gabriele Andretti (born February 28, 1940) is an American former racing driver and businessman, who competed in Formula One from 1968 to 1982, and IndyCar from 1964 to 1994. Andretti won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1978 with Lotus, and won 12 Grands Prix across 14 seasons. In American open-wheel racing, Andretti won four IndyCar National Championship titles and the Indianapolis 500 in 1969. In stock car racing, he won the Daytona 500 in 1967. In endurance racing, Andretti is a three-time winner of the 12 Hours of Sebring. Born in the Kingdom of Italy, Andretti and his family were displaced from Istria during the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus and eventually emigrated to Nazareth, Pennsylvania in 1955. He began dirt track racing with his twin brother Aldo four years later, with Andretti progressing to USAC Championship Car in 1964. In open-wheel racing, he won back-to-back USAC titles in 1965 and 1966, also finishing runner-up in 1967 and 1968. He also contested stock car racing in his early career, winning the 1967 Daytona 500 with Holman-Moody. He took his first major sportscar racing victory at the 12 Hours of Sebring that year with Ford. Andretti debuted in Formula One at the United States Grand Prix in 1968 with Lotus, where he qualified on pole position. He contested several further Grands Prix with Lotus in 1969, during which he won his third USAC title and the Indianapolis 500. In 1970, Andretti took his maiden podium finish at the Spanish Grand Prix with STP, driving a privateer March 701. He signed for Ferrari that year, winning at Sebring again. Andretti took his maiden victory in Formula One at the season-opening South African Grand Prix in 1971, on debut for Ferrari. He took his third Sebring victory the following year. After part-time roles for Ferrari and Parnelli in 1972 and 1974, respectively, Andretti joined the latter full-time for 1975 after finishing runner-up in the SCCA Continental Championship. He moved back to Lotus in 1976, winning the season-ending Japanese Grand Prix. Andretti won four Grands Prix in 1977, finishing third in the World Drivers' Championship. He won the title in 1978 after achieving six victories, becoming the second World Drivers' Champion from the United States. After winless 1979 and 1980 campaigns with Lotus, he moved to Alfa Romeo in 1981. Following his one-off appearances for Williams and Ferrari in 1982, Andretti retired from Formula One with 12 wins, 18 pole positions, 10 fastest laps and 19 podiums. Andretti returned to full-time IndyCar racing in 1982, placing third in the standings with Patrick, amongst winning the Michigan 500. After finishing third again with Newman/Haas in his 1983 campaign, he won his fourth IndyCar title in 1984, 15 years after the previous and his first sanctioned by CART. He won the Pocono 500 in 1986 and remained with Newman/Haas until 1994; his victory at Phoenix in 1993 made him the oldest winner in IndyCar history, aged 53, as well as the first driver to win a race in four different decades. Andretti retired with 52 wins, 65 pole positions and 141 podiums in IndyCar. His 111[b] official victories on major circuits across several motorsport disciplines saw his name become synonymous with speed in American popular culture. His sons, Michael and Jeff, were both racing drivers, the former winning the CART title in 1991 and previously owning Andretti Global. Andretti is set to serve on the board of directors of Cadillac in Formula One from its debut 2026 season onwards. Andretti was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2000. Early lifeChildhood in ItalyMario Gabriele Andretti was born on February 28, 1940,[c] in Montona, Istria, Kingdom of Italy (present-day Motovun, Croatia).[5][6][3] He was born six hours before his twin brother Aldo.[7] He is the son of Alvise "Gigi" Andretti, who worked as a farm administrator in Italy and for Bethlehem Steel in the U.S.,[8] and his wife Rina.[9] He also had an older sister, Anna Maria Andretti Burley.[10] Andretti's family owned a 2,100-acre farm in Montona,[11] but after World War II, the Treaty of Paris (1947) transferred the territory to communist-controlled Yugoslavia. As a result, the Andretti family joined the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus in 1948. The family lost all their land and was permitted to take only one truckload of possessions.[11] They spent seven years in a refugee camp in Lucca.[12] The Andretti twins were interested in racing at an early age. At age two, they ran around the kitchen making car noises before they had even seen a car.[6] At age five, they raced hand-crafted wooden cars through the Montona streets.[13] After moving to Lucca, the brothers got a job parking cars at a local garage.[14] In his autobiography, Andretti wrote, "The first time I fired up a car, felt the engine shudder and the wheel come to life in my hands, I was hooked."[15] The garage owners noticed the brothers' passion for racing and brought them to watch the 1954 Mille Miglia, which was won by two-time Formula One champion Alberto Ascari.[14][16] Ascari became Andretti's personal idol.[17][18] The twins also visited Monza for the Italian Grand Prix, where Andretti saw Ascari race against Juan Manuel Fangio.[18] Although the twins did not have a grandstand seat, Andretti recalled "being just mesmerized, overwhelmed by the sound, by the speed."[14] Move to the United StatesFollowing a three-year wait for U.S. visas, the Andretti family moved to the United States in 1955. After an eleven-day journey on the SS Conte Biancamano, they sailed into New York Harbor on Anna Maria's birthday of June 16.[7][19] With just $125 in cash,[6] they settled in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, where Alvise Andretti's brother-in-law Tony lived. Although Alvise planned to leave after five years, the family never left the United States.[11] Andretti opposed leaving Italy at the time.[11] His father felt that moving to America would give his children the best opportunity to succeed in life,[20] but did not want his sons to become motor racers, as the sport was extremely dangerous at the time.[11] Andretti planned to become a welder,[21] but racing was "the only passion [he] really had career wise," and he admitted that he might not have been able to become a racer if he had stayed in Italy.[20] Andretti's father did not watch him race until Andretti reached IndyCar in 1964.[22] It was initially claimed that Andretti became a naturalized U.S. citizen on April 15, 1964, four days before his IndyCar debut.[3] Andretti actually obtained U.S. citizenship on April 7, 1965.[4] Early racing careerDebut in dirt track racingThe first car Andretti regularly drove was his father's 1957 Chevrolet, which the twins frequently upgraded with features like a glasspack muffler and fuel injection.[14]  The Andretti twins were surprised to find that Nazareth hosted a half-mile dirt track, Nazareth Speedway.[6] They used money they made working at their uncle's Sunoco station[11] to refurbish a 1948 Hudson,[6] using a stolen beer barrel as a fuel tank.[11] The car was ready to race when the twins were 19 years old, but the minimum age to race was 21, so the brothers convinced a newspaper editor to falsify their drivers' licenses.[11] After Aldo got into a major accident, the local chief of police spotted the forgery but turned a blind eye to save Aldo's health insurance.[14] The twins did not tell their father about their racing activities until Aldo suffered a fractured skull during a race and spent 62 days in a coma. Andretti's father nearly disowned Mario when the latter insisted on racing again, but eventually relented.[11] Aldo also resumed racing, but suffered a career-ending accident in 1969.[11] The twins got off to a good start in racing, picking up two wins each in the Limited Sportsman Class after their first four races.[23] In their first two weeks of racing, they won $300; they had been making $45 a week at the gas station.[11] From 1960 to 1961, Mario won 21 out of 46 modified stock car races.[6] The twins raced against each other only once, at Oswego Speedway in 1967; Mario won, with Aldo finishing 10th after a brake failure.[7] To intimidate their opponents, the twins bought Italian racing suits and fabricated a story about racing in junior formulae back in Italy. Andretti maintained the fiction for many years.[24][3] In 2016, he admitted that the story was fabricated. He recalled that it "psych[ed] [the opponents] out, big time."[11] Single-seater racingDespite his early successes racing modified stock cars, Andretti's goal was to race in single-seater open-wheel cars.[3] He started by racing midget cars in the American Racing Drivers Club (ARDC) series from 1961 to 1963, starting with 3/4 (sized) midgets before graduating to full-sized midgets.[3] He raced in over one hundred events in 1963,[25] and picked up 29 top-five finishes in 46 ARDC races.[26] On Labor Day in 1963, Andretti won three feature races at two different tracks, an afternoon race at Flemington and a doubleheader at Hatfield, after which reporter Chris Economaki told him that "you just bought the ticket to the big time."[3] From midget cars, the next step on the East Coast racing ladder was sprint car racing, first with the United Racing Club (URC) series and then with the United States Auto Club (USAC) series. Andretti attempted to secure a full-time URC ride, but received only spot starts. However, USAC team owner Rufus Gray gave him a full-time drive for 1964. He finished third in the season standings to Don Branson and Jud Larson, both of whom were roughly twenty years his senior,[27] but won one race at Salem.[3] Andretti continued to race in sprint cars after progressing to IndyCar. In 1965 he won once at Ascot Park, and finished tenth in the season standings.[27] In 1966 he won five times (Cumberland, Oswego, Rossburg, Phoenix, and Salem), but finished second in the standings, behind Roger McCluskey.[27] In 1967 he won two of the three events that he entered.[3] USAC IndyCar careerFrom 1956 to 1978, the top open-wheel racing series in North America was the USAC National Championship, alternatively referred to as IndyCar or Champ Car.[28] The races were run on a mixture of paved and dirt ovals, and in later years also included some road courses. In 1971, USAC split off its dirt-track races into a separate National Dirt Car Championship. The pavement championship retained the name USAC Championship Car Series, while the dirt championship had fewer races and was later rebranded to the "Silver Crown Series."[29] Breaking in (1964)Andretti entered IndyCar during the 1964 season, while still racing full-time in sprint cars. On April 19, the Doug Stearly team gave him a spot start at Trenton Speedway.[3] He started 16th and finished 11th.[26] Andretti spent the first portion of the 1964 season trying to find a full-time IndyCar drive. An opening appeared to materialize when one of the big three IndyCar teams,[30] Dean Van Lines (DVL), lost Chuck Hulse to injury.[26] Andretti met with DVL's chief mechanic, Clint Brawner, to ask for the drive.[3] Although Andretti had come with an introduction from his sprint car team owner, Rufus Gray, Brawner turned Andretti down, as he was skeptical of sprint car racing and felt that Andretti was not ready to compete.[3][26] He hired Bob Mathouser to replace Hulse.[26] Andretti joined Lee Glessner's outfit, but was forced to sit out the 1964 Indianapolis 500.[26] Dean Van Lines, Andretti Racing, and STP (1964–1971) Andretti got his big break with DVL midway through the 1964 season, after the youngster impressed Brawner in two races: a sprint car race in Terre Haute, Indiana[3] and an IndyCar race at Langhorne Speedway, where Andretti passed Mathouser in the closing laps.[26] Andretti was pleased to join what he called one of the "few outfits worth driving for."[31] He completed the final eight races of the season with DVL, finishing 11th in the season standings.[3] He was named IndyCar Rookie of the Year.[32] The Andretti-Brawner combination would soon come to dominate the sport, staying together through two ownership changes until Brawner left at the end of 1969.[33] From 1965 to 1969, Andretti won three USAC IndyCar titles. He also came within 93 points of winning five in a row; for comparison, at the time, 100 points was the difference between finishing sixth and seventh at the Indianapolis 500. At the peak of his statistical dominance, Andretti won 29 of 85 USAC championship races between 1966 and 1969.[6] In 1965, Andretti's first full season with DVL, he took advantage of the team's new Brawner Hawk, a derivation of the Brabham Formula One chassis.[26] His third-place finish at the 1965 Indianapolis 500 earned him the race's Rookie of the Year award.[26] He won his first IndyCar race at the Hoosier Grand Prix.[3] Although he won only one race that year, he scored six second places and three third places, and scored points in 16 out of 18 races. His closest competitor, A. J. Foyt (who had won four of the last five USAC titles) won five races but failed to score seven times. At age 25, Andretti became the youngest IndyCar champion in history,[25] a record he held for thirty years until Jacques Villeneuve won the 1995 title.[26] To his irritation, however, when he appeared on Johnny Carson at the end of the season, he was introduced as the Indy 500 Rookie of the Year, which he felt downplayed his title win.[26] In 1966, Andretti won his second straight USAC title. In contrast to his maiden title win, Andretti won eight of fifteen events[3] and led 1,142 laps, nearly 1,000 laps more than his closest competitor.[26] He led 54.5% of all laps in 1966, an record until Al Unser's 66.8% in 1970, and still the second-highest figure in history as of the 2022 season.[34] Andretti also took pole at the 1966 Indianapolis 500, but retired after 27 laps with a mechanical failure.[3] In 1967, Andretti lost the season USAC championship to A. J. Foyt. Although Andretti won eight races, Foyt won the 1967 Indianapolis 500;[35] Andretti was on pole at Indianapolis but lost a wheel.[36] Andretti fought through broken ribs to stay in the title race.[36] Foyt carried a 340-point lead over Andretti going into the season-ending Rex Mays 300 at Riverside.[36] Andretti ran out of fuel with four laps to go and settled for third,[36] costing him 180 points.[37] Ordinarily, he would have won the championship anyway, as third place was worth 420 points and Foyt had crashed on lap 50.[37] However, Foyt's tire sponsor Goodyear arranged for him to commandeer Roger McCluskey's car to prevent Andretti, a Firestone man, from winning.[36] Foyt piloted McCluskey's car to fifth place. Despite a point deduction, he won the championship by 80 points.[38] Andretti was named Driver of the Year due to his successes in multiple categories, but felt disappointed, saying, "I had the championship in my hands, and then it was gone."[36] DVL owner Al Dean died at the end of the 1967 season. Per his wishes, the team was wound up and its cars were sold to Andretti, who became an owner-driver under the name Andretti Racing Enterprises.[33] Brawner stayed on as chief mechanic.[39] In 1968, Andretti once again lost the title at the final race of the season at Riverside, but this time in a reversal of the events of 1967. Andretti held a 304-point lead over Bobby Unser at the start and led Unser on track by 47 seconds at one point. However, his engine failed on lap 58. He borrowed Joe Leonard's car (which he crashed) and then Lloyd Ruby's car for the final 47 laps. He fought back to third, but the 420 points for third place were reduced by a ratio of 47/116. Meanwhile, Unser finished second, scoring 480 points. Unser won the title by 11 points, an "almost unbelievable" margin of victory.[38] Despite losing the title, Andretti set records for second-place finishes in a season (11 times in 27 starts) and podium finishes in a season (16), which still stand to this day.[34]

Unhappy about being an owner-driver,[40] and concerned that Firestone was cutting back its sponsorship budget,[35] Andretti sold the team to Andy Granatelli's STP Corporation before the 1969 season. Granatelli retained the DVL cars and staff,[33] although Brawner disliked Granatelli and insisted that he not participate in racing decisions.[41] Andretti won nine races in 1969, including the 1969 Indianapolis 500 and the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.[23] He won his third title and was named ABC's Wide World of Sports Athlete of the Year.[42] His 5,025 points were a USAC record, and he scored nearly twice as many points as runner-up Al Unser (2,630).[35] The core of the team split up after the 1969 title season, when mechanics Clint Brawner and Jim McGee left STP to start their own team.[33] Andretti remained with STP, which agreed to sponsor him during the 1970 Formula One season.[43] Following the split, it was said that Brawner and McGee felt underpaid by the new management.[33] However, it was also rumored that Andretti forced out Brawner, although Andretti and McGee both said that Brawner did not want to deal with Granatelli.[40][41] McGee said that Andretti and Brawner had been "feuding for years,"[44] but "certainly respected each other."[40] He opined that Brawner quit after Granatelli intervened on Andretti's side during a dispute, breaking his promise to remain uninvolved.[44] According to an urban legend, Brawner's wife Kay hexed Andretti's family after the STP split, giving rise to the so-called "Andretti curse."[40] Neither side fully recovered from the split. The Brawner/McGee team folded midway through the 1972 season.[33] Meanwhile, Andretti settled for a fifth-place finish in 1970,[45] and the STP Formula One team shut down after five races. In 1971, after dirt tracks were split into a separate championship, Andretti fell to ninth in USAC's paved track championship.[45] He scored no points in the dirt track standings, with a best finish of 13th.[45][46] Parnelli (1972–1975)For the 1972 season, Andretti left STP and joined Vel's Parnelli Jones Racing. He recruited McGee to join him.[33] Parnelli was IndyCar's dominant team at the time, with stars Al Unser and Joe Leonard. Andretti's arrival was billed as creating a "superteam," but Andretti never won a title with Parnelli.[47] Andrettti's 1972 season was disappointing by his standards, as he finished eleventh in the pavement championship, while his teammate Leonard won the title.[45] (He did not compete on dirt tracks that year.[45]) In 1973, he finished second in the dirt-track championship,[48] which Al Unser won even though Andretti won two of the three races.[49] He also finished fifth in the main championship.[3] In 1974, he won the dirt-track championship by taking three of the five races,[48][49] but fell back to 14th in the main championship.[45] During this period Andretti was increasingly drawn to formula racing. He competed part-time in Formula One, and also raced in the North American Formula 5000 series in 1974 and 1975, both times finishing second to Brian Redman.[50] In each season, he won as many races as Redman. However, he suffered from reliability issues.[51][52] After 1974, Andretti stopped competing full-time in IndyCar to focus on Parnelli's Formula One project. After Parnelli left Formula One in 1976, it released him from his USAC contract to allow him to focus on Formula One.[53] Penske (1976–1978)While racing with Team Lotus, Andretti appeared sporadically in IndyCar with McGee's new team, Penske Racing.[44] In nineteen races from 1976 to 1978, he won one race (at Trenton in 1978) and collected eight top-five finishes.[45][54] Stock car racing careerAt the height of his Champ Car career, Andretti also made thirty appearances in top-level stock car racing, competing in sixteen USAC races and fourteen NASCAR Grand National Series races from 1965 to 1969. He finished in the top five in exactly half of his USAC races.[45] He was less successful in NASCAR, with one top-five finish and three top tens, but won the competition's most prestigious race, the 1967 Daytona 500.[55] As of 2017, Andretti and A. J. Foyt were the only non-full-time stock car drivers to ever win the Daytona 500.[55] In USAC, Andretti finished twelfth in the 1965 standings after participating in five out of sixteen races.[56] His best season performance was 1967, when he competed in eight out of 22 races, won round 12 at Mosport, and finished seventh in the season standings.[57] Following USAC's split between road course and dirt course standings, he won three road course races in 1974 and another four in 1975.[3] In NASCAR, Andretti spent 1966 guesting with various teams before obtaining a consistent three-season guest role with Holman-Moody, his sportscar racing team, which also served as the Ford works team.[58] His appearances were mainly limited to Daytona (eight races) and Riverside (four races). As a guest driver, Andretti did not receive the first pick of equipment and pit crews,[58] and he won only one race, the 1967 Daytona 500, where he persuaded Holman-Moody to give him a top-spec engine.[58] He later claimed that the team tried to sabotage his race so that its lead driver, Fred Lorenzen, could inherit the win,[58][59] and noted that he needed to get tips on setting up the car from a rookie, Donnie Allison.[59] (His future team owner, Parnelli Jones, agreed with the sabotage allegation, quipping that "I don't think I've ever seen a team not want its driver to win [before]."[55]) Andretti stopped competing in NASCAR after 1969, as race seats at teams of the caliber of Holman-Moody rarely came open after the 1960s.[60] In the 1970s and 1980s, Andretti competed in six editions of the International Race of Champions (IROC), an invitational stock car series with a limited calendar. He won IROC VI and finished second in IROC III and IROC V. He won three races in twenty events.[61] Formula One careerPart-time roles (1968–1970) Although the Indianapolis 500 dropped off the Formula One calendar in 1960, some teams continued racing at Indianapolis, including Colin Chapman's Team Lotus.[62] At the 1965 Indianapolis 500, Lotus star Jim Clark won and Andretti finished third as the top-placed rookie.[63][64] On Clark's recommendation,[65] Chapman invited Andretti to race in Formula One, saying, "When you're ready, call me."[64][62] Andretti joined Lotus for the 1968 Italian Grand Prix.[66] He was delighted by the Lotus 49B, saying that its handling was a major improvement over IndyCar.[65] He beat the Monza lap record in testing,[66] but was contractually obligated to fly back to America for a race in Indiana, and was disqualified for doing so.[66] He later said that the race officials broke a promise to waive the applicable rule on his behalf.[67][62] Andretti got his real start in Formula One at the 1968 United States Grand Prix and took pole.[63][68] Due to his disqualification at Monza (where he had qualified tenth),[69] he became the first Formula One driver to start his first race from pole.[65] Jackie Stewart overtook him on the first lap, but the two drivers were neck-and-neck until Andretti's nose cone broke, forcing him to pit. He eventually retired with a clutch failure, but he had made a strong impression. Reviewing the race, Motor Sport wrote that Andretti displayed "that same assurance of absolute control [in the corners] one saw in [Jim] Clark's driving."[70] At the end of the 1968 season, Chapman offered Andretti a full-time drive to replace Clark, who had died in an accident that April. Andretti declined, not wishing to give up his stable USAC career. For the next four years, he made only sporadic appearances in Formula One with Lotus, STP-March, Ferrari, and Parnelli.[63] The cars were mostly uncompetitive, and he failed to finish seven out of eight races in 1969 and 1970. At the one race he finished, the 1970 Spanish Grand Prix, he collected his first Formula One podium after several drivers ahead of him retired with mechanical issues.[71] Ferrari (1971–1972)Andretti signed with Ferrari in 1971 and entered seven out of 11 races, completing two. In his Ferrari debut, he won his maiden Grand Prix at Kyalami after race leader Denny Hulme's engine failed with four laps to go.[72] He also won the non-championship Questor Grand Prix in California.[73] Following the Questor win, Enzo Ferrari offered to make Andretti his No. 1 driver for 1972, but Andretti declined, later remarking that "[Formula One] didn't pay much back then [...] but I always figured I'd get another opportunity."[74] Andretti also raced five times in 1972, but scored no podiums. He did not compete in the 1973 season.[citation needed] Parnelli (1974–1976)In the mid-1970s, Andretti encouraged Parnelli, his IndyCar team, to sponsor a Formula One car.[75] He had previously persuaded the team to hire Lotus designer Maurice Philippe.[76] To prepare for a Formula One challenge, the team secured funding from Firestone,[75][62] which agreed to make special tires for the team.[47] The team hired more Lotus veterans, including Jim Clark's old crew chief Dick Scammell and administrator Andrew Ferguson.[76] Parnelli ran Andretti in the two North American end-of-season races in 1974.[62] He qualified third at the United States Grand Prix but did not start the race due to a mechanical failure.[76][47] In 1975, Andretti drove a full Formula One season for the first time, skipping two races to compete in IndyCar.[77] He was disappointed by the Parnelli VPJ4, which he felt was derivative of the Lotus 72. More importantly, sponsor Firestone pulled out ahead of the season.[76] The VPJ4 had been designed for Firestone's custom tires, and without them, its performance suffered.[47] The car also suffered from frequent brake failures.[78] At the Spanish Grand Prix, Andretti qualified fourth and reached first with the help of a multi-car crash on the first lap. However, the crash damaged his suspension, forcing his eventual retirement.[79] He finished third at the non-championship 1975 BRDC International Trophy Race.[76] At the Swedish Grand Prix, he was nearly killed when his brakes failed during qualifying, but finished fourth with the team's backup car.[47] He finished 14th in the Drivers' Championship, scoring five points.[citation needed] Parnelli skipped the first race of the 1976 season,[78] so Andretti started the year with Lotus and returned to Parnelli for the next two races.[80][62] Parnelli pulled out of Formula One after round three when sponsor Viceroy withdrew funding.[25] Andretti only learned of the decision when a reporter asked him about it as the grid lined up to start the race.[78][47] He later admitted that "I was the only one, really, that wanted [the Formula One team]."[62] For his own part, Parnelli Jones maintained that he did not make money on the venture and tried to give Andretti a good car.[78] Lotus (1976–1980)1976 The day after Andretti learned Parnelli was shutting down, he met Lotus' Colin Chapman, who told him, "I wish I had a decent car for you."[62][78] Andretti took the Lotus job anyway, promising Chapman that "we will make the car better."[47] He negotiated for number one driver status, mindful of Chapman's reputation for giving only one driver the best machinery.[62] On at least one occasion, he exercised his authority to borrow his teammate's car when it was faster at a particular circuit.[81] The Lotus 77 was not competitive, and with five races to go, Andretti had scored just five points, leaving him mired in 13th place.[82] At the next race, the Dutch Grand Prix, Andretti scored his first podium since March 1971. He collected three podiums in the final five races and lapped the field in his victory at the season-ending Japanese Grand Prix.[63] The late-season flurry of results moved Andretti up to 6th in the Drivers' Championship, with 22 points.[citation needed] Ground effect revolution Andretti's timing was fortuitous, as he rejoined Lotus at the eve of the ground effect revolution. Since mid-1975, Lotus had been trying to shape the car to generate downforce (making the car faster in the corners) without a large rear wing (whose drag would make the car slower on the straights). The Lotus design team added sidepods with vents to take in air, which was then channeled under the floor to facilitate the Venturi effect. The car was effectively sucked towards the ground, allowing it to take corners at unusually high speeds.[83] Andretti, whose STP-March team had experimented with sidepods in 1970,[84] encouraged the team to make the sidepods even bigger.[85] Andretti took a close interest in developing the car.[85] He knew that Lotus had a reputation for building dangerous cars and worked with his mechanics to ensure that Chapman did not do anything "too radical."[14] Wind tunnel technology was still primitive at the time, but Lotus devised a way to model air flow on track by hiring a photographer to take pictures of wind-sensitive bristles that were mounted on the chassis in tests.[85] While testing the car at Hockenheim, Andretti noticed that the car's downforce was much stronger when he drove close to a nearby fence. Chapman added sideskirts to keep the air flowing in one direction.[85][86] Andretti also helped the team with his ability to set up a car; one commentator said that "aside from Andretti, only Lauda was known for great technical understanding [...] an increasingly vital quality for racecar drivers as racecars became increasingly sophisticated."[87] Drawing on his extensive oval racing experience in the U.S., Andretti optimized his cars for each track by exploiting subtle differences in tire size ('stagger') and suspension set-up ('cross weighting') on each side of the car.[88][89] Engineer Nigel Bennett recalled that Andretti would request seemingly imperceptible adjustments to the car, such as "Lower the front springs by an eighth of a turn."[90] 1977: Reliability issues In 1977, the Lotus 78 "wing car" was one of the fastest cars on the grid, and Andretti won four races, more than any other driver. At the Belgian Grand Prix, Andretti took pole by 1.54 seconds, infuriating Chapman, who did not want other teams to know just how good the car was.[83] Andretti failed to win that race, as he crashed into John Watson, which he called "one of the biggest mistakes of [his] career".[11] At round four, Andretti won the United States Grand Prix West.[91] He scored a dominant win at the Spanish Grand Prix,[92] but also held his own under close racing, winning the French Grand Prix after a dramatic last-lap pass on Watson.[93] He also won his first Italian Grand Prix after three attempts, an achievement in which he took great pride.[94][11] Andretti concluded that the Lotus 78 was his favorite Formula One car, even more than the next year's title-winning Lotus 79.[95] Andretti endured a snakebit season, with exceptionally poor reliability. Lotus had commissioned special engines, which proved to be unreliable,[83] and Andretti suffered engine failures while leading at Spielberg,[96] in second at Silverstone,[97] and battling for third at Zandvoort.[98] His engine also failed at Hockenheim.[99] Lotus' Peter Wright and Ralph Bellamy felt that if Chapman had settled for a regular Cosworth DFV engine, Lotus would have won the title.[90][100] For his own part, Andretti rued Chapman's tendency to "pull the last litre or two of fuel out of the cars before the race," noting that he ran out of fuel at three races in 1977 (Kyalami, Anderstorp, and Mosport).[101] Andretti also retired in third at Interlagos with an electrical failure.[102] Ferrari dominated the Constructors' Championship with 95 (97)[d] points to Lotus' 62, and Andretti finished third in the Drivers' Championship, with 47 points, 25 behind Ferrari's Niki Lauda, who skipped the last two races.[103] 1978: World Champion Andretti won his first and only Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1978. Before the season, the team signed Ronnie Peterson and made him the highest-paid driver in Formula One.[74] Although Chapman agreed to pay Andretti the same salary,[74] Andretti felt that he had earned number one driver status given how much time he had invested to develop the car.[105] Enzo Ferrari offered to double Andretti's salary, but withdrew the offer after Chapman "raised hell with [Enzo]".[74] Chapman placated Andretti by offering him a bonus of $10,000 a point.[74] In addition, Chapman promised to impose team orders to give Andretti the lead if Lotus was leading 1–2.[105] The team stayed with the 78 for the first five races while Chapman perfected the next car. At the season-opening Argentine Grand Prix, Andretti took pole and led from start to finish.[106] After five races, he was tied for second place in the standings with 18 points, five adrift of Patrick Depailler.[107] Lotus unveiled the Lotus 79 at the Belgian Grand Prix. The new car included an improved diffuser to facilitate airflow at the back of the car.[85] With plenty of downforce in hand, Lotus ran a small rear wing that increased the car's top speed,[108] fixing what Andretti felt was the 78's biggest weakness.[84] The 79 did introduce a new weakness, as a design flaw overheated the brake fluid.[85] Andretti's smooth driving style suited the car, whose downforce was so great that the chassis might have buckled in the hands of a more choppy driver.[85] At Belgium, Andretti took pole by eight-tenths of a second, led from start to finish, and won by ten seconds.[90] Andretti dominated the rest of the season, winning five of the next eight races, while teammate Peterson finished second with two wins.[103] Lotus had four 1–2 finishes in 1978, and Andretti won them all, generating speculation that Chapman had ordered Peterson to let Andretti win.[109] Two rounds before Andretti clinched the title, Peterson denied being ordered to let Andretti by.[110] However, he then "ostentatiously" followed Andretti to a 1–2 finish at Zandvoort.[25] Andretti clinched the championship at the Italian Grand Prix, with two races to go.[6] He did not celebrate, as Peterson had suffered a major crash; he died later that night.[6] In 2018, Andretti said that "I could never truly celebrate and I never will. It was an enormous jolt. You never really totally recover from [it]."[85] 1979–1980Andretti never won another Grand Prix after 1978. Following the 1978 title season, lead sponsor Imperial Tobacco pulled funding until 1983.[111] In 1979, the team rolled out the Lotus 80, whose downforce overwhelmed the car's suspension, generating porpoising issues, and whose weak chassis popped out rivets while driving.[112] Andretti scored a podium in the Lotus 80's debut at Jarama.[25] His new teammate Carlos Reutemann refused to drive the car at all, and Andretti drove it only three times before returning to the Lotus 79, which was already out of date.[113][114] Andretti finished 12th in the standings, with 14 points. It was the first time in his full-time Formula One career that he finished behind his teammate. Reutemann left for Williams after the season.[113] Following the failure of the Lotus 80, Chapman tried to solve the problem by developing the Lotus 88, a complex and innovative carbon-fiber, dual-chassis structure.[115] In theory, one chassis would absorb the porpoising while the other chassis would carry the driver.[116] The team used a transitional car, the Lotus 81, for 1980, while Chapman developed the 88. Lotus replaced Reutemann with two talented teammates, Elio de Angelis and (briefly) Nigel Mansell, but the team was again unsuccessful.[117] Andretti scored only one point all season. Over the course of the season, he lost faith in the developing Lotus 88, declaring that Chapman "got bored and started going crazy with other things that were outside of the rules."[118] He left Lotus at the end of the season, shortly before Chapman was about to unveil the Lotus 88 for 1981. After his departure, the FIA banned the Lotus 88.[118] Alfa Romeo (1981) For the 1981 season, Andretti had a choice between Alfa Romeo and McLaren. He picked the Italian team due to his friendship with one of their engineers[118] and the higher salary on offer.[25] Before the 1981 season, the FIA outlawed sliding sideskirts, which the Alfa Romeo design team had relied on to generate ground effect.[119] Andretti finished fourth on his debut at the United States Grand Prix West, but the team was otherwise uncompetitive.[118][120] Andretti finished 17th in the Drivers' Championship, with 3 points. He left the team after the season, explaining that the new generation of Formula One cars required "toggle switch driving with no need for any kind of delicacy [...] it made leaving Formula One a lot easier than it would have been."[121] Stand-in appearances (1982)During the 1982 season, Andretti briefly raced for both the Drivers' and Constructors' Championship-winning teams, Williams and Ferrari. Andretti joined Williams for the United States Grand Prix West after Reutemann abruptly quit. He damaged his suspension after contacting a wall and retired.[122] IndyCar commitments prevented him from signing a full-time contract,[122] and Williams' Keke Rosberg won the Drivers' Championship.[123] Andretti then replaced the injured Didier Pironi at Ferrari for the last two races of the season. He took pole and finished third at the Italian Grand Prix.[124] At the season-ending Caesars Palace Grand Prix, Andretti's final Formula One race, he retired with a suspension failure, but Niki Lauda's engine failure clinched the Constructors' Championship for Ferrari.[123] Andretti agreed to serve as Renault's reserve driver for one U.S. race in 1984,[125] but declined to be considered for a reserve role in 1986, effectively ending his Formula One career.[126] CART IndyCar careerPenske (1979–1980) In 1979, a new organization, Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART), set up the IndyCar World Series,[127] which displaced the USAC championship.[28] CART was formed because the larger and more institutional IndyCar teams, like Andretti's Penske Racing, wanted the sport to emphasize technical innovation (the costs of which deterred new entrants) and a more structured commercial strategy.[28] After Penske helped start CART, Andretti sporadically competed in CART during the 1979 and 1980 seasons, winning one race at Michigan in 1980.[128] Patrick (1981–1982)Andretti switched to Patrick Racing for the 1981 season. The move reunited him with STP Corporation, the team's sponsor, and Jim McGee, Andretti's mechanic from DVL and Parnelli.[129] He did not win a race, but recorded five top-five finishes in seven races; the other two results were mechanical DNFs.[130] At the 1981 Indianapolis 500,[e] Andretti was controversially stripped of the win four months after the race.[131] After leaving Alfa Romeo, Andretti joined CART full-time for the 1982 season. He finished third in the season standings, with six podiums in 11 races. As with 1981, all his other results were mechanical DNFs.[132] Newman/Haas (1983–1994)In 1983, Andretti joined the new Newman/Haas Racing team, set up by Carl Haas and actor (and former Can-Am team owner) Paul Newman.[133] The team used cars built by British company Lola, in contrast to the March cars in vogue at the time.[134] The team lured Andretti by promising to run only one car, making him the focus of the team.[133] Andretti spent the rest of his full-time racing career with Newman/Haas.[25] Solo-racer eraIn 1983, Andretti worked with the team to develop the uncompetitive Lola T700 into a decent car.[135] At round six, he took the team's maiden win at Elkhart Lake, and scored another win in Las Vegas. He recorded eight top-five finishes in 13 starts.[136]  In 1984, the team commissioned a new chassis, which became the Lola T800. The car was designed by Lotus veteran Nigel Bennett and used the ground effect technology that Formula One had just banned in 1982.[134][137] However, the team got off to a mediocre start. Andretti won the season opener at Long Beach, but his Indianapolis 500 race was compromised by electrical issues, and his wheel fell off at the Milwaukee Mile. After four races, he trailed Tom Sneva by 58 points.[135] In mid-season, however, he won five out of eight races. After a tight, season-long battle, Andretti closed out the season with two conservative second-place drives, explaining that "I hated driving that way but that's what I had to do."[135] He beat Sneva by 13 points to claim his fourth IndyCar title at the age of 44.[25] At the end of the season, he was voted Driver of the Year for a third time.[135] The team took a step back in 1985. Other teams noticed that in addition to Andretti's six wins, Danny Sullivan won three races in a customer T800.[134] To make more money, Newman/Haas agreed to distribute the Lolas to more competitors, watering down its technical advantage.[138] Andretti got out to a fast start, winning three of the first four races and finishing second in the fourth, the 1985 Indianapolis 500. After four races, he had a 34-point lead in the standings.[139] However, he recorded only one more top-five finish the rest of the way, and finished fifth in the standings.[140] From 1986 to 1988, Andretti's son Michael emerged as a force in the sport. In 1986, Michael placed second, beating Mario for the first time. Father and son both scored five poles.[25] At round five in Portland, Mario beat Michael by 0.07 seconds, the closest finish in IndyCar history.[141] In addition, at age 46, he finally won his home race, the Pocono 500, after 14 attempts.[142][143] He called it "one of the happiest weekends [he had] ever had."[144] He led the championship with ten races to go,[144] but did not pick up another podium the rest of the way.[145] In 1987, with an Adrian Newey-designed chassis and new engines designed by Ilmor,[146] Andretti picked up eight poles but converted them into two wins.[25] He dominated the Indianapolis 500 but dropped out with a blown engine late in the race.[133] At the following race at Milwaukee, he passed A. J. Foyt for the all-time lead in career laps led. However, he crashed when his rear wing came loose and injured his neck. He called it "the hardest hit I've ever taken."[147] In 1988, Andretti finished fifth in the season standings, one spot ahead of Michael.[25] He picked up two wins, but continued to suffer from reliability issues and was involved in several costly accidents.[148] Two-car eraMichael Andretti joined Newman/Haas in 1989, which added a second car for the first time to accommodate him.[25] Mario and Michael became the first father/son team to compete in both IMSA GT and Champ Car racing.[24] Michael reached the peak of his career, winning the 1991 championship and finishing second in 1990 and 1992. By contrast, Mario performed well but not brilliantly. During the 63 races from 1989 to 1992, he scored 30 top-five finishes but recorded no wins.[45][25] Ahead of the 1993 season, Michael Andretti left CART for Formula One.[149] Mario wanted to return to the old one-car system, but the team replaced Michael with the reigning Formula One champion, Nigel Mansell, and gave Mansell number one driver status. Mansell and Andretti raced as teammates for two years, but did not get along, owing to their mutual competitiveness and personality differences.[150] Andretti scored his last IndyCar win during the 1993 Phoenix race.[151] At 53 years and 34 days old, he became the oldest recorded winner in an IndyCar event.[151][152] Later that year, he qualified on pole at the Michigan 500 with a speed of 234.275 miles per hour (377.029 km/h), setting a new closed-course world record.[25] He finished sixth in the season standings, while Mansell won the title.[citation needed] Andretti decided to race one final season, dubbed "The Arrivederci Tour." In 1994, the team as a whole took a step back, and Newman/Haas went winless for the first tim. At his 407th, and final, IndyCar race, at Laguna Seca, Andretti's race was initially derailed by a flat tire, but he weaved his way back up to seventh. His engine failed with four laps to go.[153][25] At the time of his retirement, his 52 wins were the second-most in history, behind only A. J. Foyt's 67. (Scott Dixon passed him in 2022.)[154] In addition, his 7,595 laps led remain the all-time record, nearly 1,000 laps higher than second-placed Michael Andretti's 6,692.[34] Indianapolis 500Andretti won once at the Indianapolis 500 in 29 attempts, and finished all 500 miles (800 km) just five times in his career. He had so many incidents and near victories at the track that critics have suggested the existence of an "Andretti Curse."[155][156] Andretti occasionally did well at Indianapolis. He won the 1969 race, but benefited from good luck: he completed the race in the team's backup car, a now-outdated Brawner Hawk, and on just one set of tires. His race engineer said that Hawk's gearbox was failing and that the car would not have lasted another five laps.[41] Andretti was also the first driver to exceed 200 miles per hour (320 km/h), during practice for the 1977 race.[21] Starting in 1981, Andretti encountered several out-of-the-ordinary instances of bad luck at the Indianapolis 500:

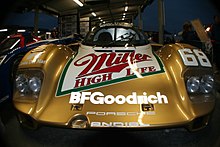

Andretti's last race at Indy was the 1994 Indianapolis 500, where he dropped out due to mechanical issues.[155] His last major on-track participation came at the 2003 Indianapolis 500, when his son Michael invited him to test the injured Tony Kanaan's car. The 63-year-old Andretti ran at competitive speeds, but when Kenny Bräck crashed in front of him, Andretti ran over Bräck's debris and went airborne, leading to a "spectacular" crash. He escaped with minor injuries.[25] Reflecting on the curse in 2019, Andretti noted that while he "think[s] about all the times [he] should have won here," he also won in 1969, "when everything went wrong."[41] Sportscar racing careerNorth American endurance racingAndretti's first race in a sportscar was in 1965, when he piloted a Ferrari 275 P at the Bridgehampton 500 km at Bridgehampton; he did not finish.[162] Andretti won three 12 Hours of Sebring endurance races (1967, 1970, 1972),[6] and a 6-hour race at Daytona in 1972.[163] In early sportscar races he competed for Holman-Moody, but later often drove for Ferrari.[162] Andretti signed with Ferrari in 1971, and won several races with co-driver Jacky Ickx.[63] In 1972, he shared wins in the three North American rounds of the championship and at Brands Hatch in the UK, helping Ferrari to a dominant victory in that year's World Championship for Makes.[164] He also competed in 25 North American Can-Am races in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with a best finish of third place at Riverside in 1969.[162] Le MansAndretti competed at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in four decades. In 1966, he shared a Holman-Moody Ford Mk II with Lucien Bianchi. They retired due to valve failure.[165] In 1967, during a 3:30 am pit stop, a mechanic accidentally installed a front brake pad backwards, causing Andretti's breaks to lock up at the Dunlop Bridge. He crashed, broke several ribs,[166] and was left exposed to oncoming traffic, but Roger McCluskey pulled him to safety.[167][168]  Andretti did not return to Le Mans until ending his full-time Formula One career. In 1982, he partnered with son Michael in a Mirage M12 Ford. They qualified in ninth place, but although their car passed initial inspection several days earlier,[169] it was disqualified shortly before the race started due to an improper oil cooler.[166] They returned the following year and finished third in a Porsche customer car, behind two works Porsches.[25] The Andrettis returned in 1988 with Mario's nephew John added to the family team. Although they obtained a factory Porsche 962, one of the car's engine cylinders failed,[166] and the team finished fifth.[25] Following Andretti's retirement from full-time racing, he decided to try for another Le Mans victory, joiningCourage Compétition from 1995 to 1997. In 1995, the team qualified third, but Andretti was brake-checked by the car in front of him and crashed, forcing him to pit and costing the team six laps. The team eventually rallied from 25th to second.[25] Andretti later said that the team "lost [the 1995] race five times over" through poor organization, including a botched pit stop, an ill-considered switch to wet-weather tires, and a two-minute pit stop to wash the car to clean up the sponsor decals.[166] Porsche withdrew active support from Courage in 1996,[166] and the team finished 16th after losing 90 minutes in the pits fixing an electronic issue and a broken axle.[25] In 1997, the "now ancient Courage" was a backmarker and the team did not finish the race.[25] Andretti's final appearance at Le Mans was at the 2000 race, six years after his retirement from full-time racing. The 60-year-old Andretti drove the Panoz LMP-1 Roadster-S to a 15th-place finish.[170] Awards and honorsLegacy

Over the course of his long career, Andretti won over 100 races on major circuits, although the exact numbers vary depending on the definition of a major circuit. The International Motorsports Hall of Fame puts the total at either 109 or 111,[172][173] while Andretti and the Automotive Hall of Fame put the total at 111.[171][174] Andretti's name has become synonymous with speed in American popular culture.[175] An extremely versatile driver, Andretti stands alone, or close to it, in several lists of drivers to win in multiple categories:

With his final IndyCar win in April 1993, Andretti became the first driver to have won IndyCar races in four different decades[151][25] and the first to win automobile races of any kind in five.[6] As of 2024, Andretti's victory at the 1978 Dutch Grand Prix is the most recent Formula One win by an American driver.[178] AwardsIn 2000, Andretti was named Driver of the Century by the Associated Press and RACER magazine.[179] In 1992, he was voted the U.S. Driver of the Quarter Century by a panel of journalists and former U.S. Drivers of the Year.[180][181] He was named the U.S. Driver of the Year in 1967, 1978, and 1984,[182] and is the only driver to be Driver of the Year in three decades.[23] Andretti has also been inducted into a variety of motorsports hall of fames, including the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2000.[183] Other halls of fame include the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame (1986),[184] the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (1990),[185] the U.S. National Sprint Car Hall of Fame (1996),[3] the Automotive Hall of Fame (2005),[186] the FIA Hall of Fame (2017),[187] and the U.S. National Midget Auto Racing Hall of Fame (2019).[184] In 2019, the city of Indianapolis renamed a street "Mario Andretti Drive" to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his first Indianapolis 500 win.[188] In 2007, the Vince Lombardi Cancer Foundation awarded Andretti its Lombardi Award of Excellence.[189] In 2008, the Simeone Foundation awarded Andretti its Spirit of Competition Award.[190] Italian-American heritageOn October 23, 2006, the Italian government made Andretti a Commendatore of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (OMRI), the most senior Italian order of merit, in honor of Andretti's racing career and commitment to his Italian heritage.[179] In 2008, Andretti was also named the honorary mayor of an association of Italian exiles from Andretti's birthplace of Montona.[191][192] Andretti has also received the Carnegie Corporation's Great Immigrants Award (2006, the inaugural class);[193] the Italy–USA Foundation's America Award (2015);[194] and honorary citizenship of Lucca, Italy (2016).[195] Personal life Andretti lives in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, on an estate that he named "Villa Montona" in honor of his birthplace.[12] His late wife Dee Ann (née Hoch)[196] was a native of Nazareth. They met when Dee Ann was teaching Andretti English in 1961.[21][197] They were married on November 25, 1961, and had three children: Michael, Jeff, and Barbara, and seven grandchildren.[3][5] Dee Ann died on July 2, 2018, following a heart attack.[198] Andretti racing familyBoth of Mario Andretti's sons, Michael and Jeff, were auto racers. Michael joined CART in 1983 and won the 1991 title; he also finished second on five occasions.[199] He was U.S. Driver of the Year in 1991,[200] and was third on the all-time IndyCar career wins list when he retired.[201] Jeff Andretti competed in CART from 1990 to 1994.[202][203] Mario's nephew John Andretti competed in CART and NASCAR, winning one CART race in 1991 and two NASCAR races in 1997 and 1999.[204] In addition, in 2006, Mario's grandson Marco won the Indy Racing League Rookie of the Year award[203] and the Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year Award, as Mario, Michael, and Jeff had done before him.[205][206] During the 1991 CART season, the Andrettis became the first family to have four relatives compete in the same series.[23] In addition, the Andrettis have competed as a team in endurance racing. Mario, Michael, and John finished 6th at the 1988 24 Hours of Le Mans.[25] Mario, Michael, and Jeff finished 5th at the 1991 Rolex 24 at Daytona.[207] Business Following his retirement, Andretti has remained active in the racing community. He serves on the board of the Cadillac Formula One team,[208] which will join Formula One in 2026.[209] Since 2012, Andretti has been the official ambassador for the Circuit of the Americas (COTA) and the United States Grand Prix.[210] In the media, Andretti test drives cars for Road & Track and Car and Driver magazines[175] and has penned a racing column for the Indianapolis Star.[211] Andretti was involved with the now-defunct Champ Car World Series. He intervened to keep Champ Car at the Road America circuit following legal disputes between Champ Car and Road America management. As a result, the Road America race was renamed the "Mario Andretti Grand Prix of Road America" in his honor.[13] He also participated in the 2006 Bullrun race across the United States.[175] The first pitstop was at the Pocono Raceway in Andretti's home state of Pennsylvania, with Gate No. 5 named Andretti Road.[212] Andretti's business interests extend beyond racing. When he retired at age 54, his personal fortune was estimated at $100 million.[7] In 1995, he saved a struggling Napa Valley vineyard and renamed it the Andretti Winery.[12] He was interviewed about his winemaking activities for the documentary A State of Vine (2007).[213] In 1997, he founded Andretti Petroleum, which owns a chain of gasoline stations and car washes in Northern California.[12][214] He also owns a chain of go-kart tracks.[215] He was the title character of several video games, including Mario Andretti's Racing Challenge (1991),[216] Mario Andretti Racing (1994),[217] and Andretti Racing (1996/1997), the latter in association with his sons.[218] Film and television appearancesAndretti has contributed to several racing films. He is a major character and sometime narrator of The Speed Merchants (1972).[219] He also drove an IndyCar in the IMAX film Super Speedway (1996).[220] He also appeared in the documentary Dust to Glory (2005), which discusses a race in which he served as grand marshal.[221] In November 2015, he appeared on the first season of TV series Jay Leno's Garage, driving Leno in multiple fast cars and talking about his racing career.[222] Andretti has also made cameo or guest appearances in other media, generally associated with racing. Like many other IndyCar drivers, he guested on the television show Home Improvement.[223] He cameoed in Bobby Deerfield (1977);[224] Pixar's Cars (2006) (an animated film where he was represented by a sentient version of the Ford Fairlane in which he won the 1967 Daytona 500);[225] and DreamWorks' Turbo (2013) (where he voiced the traffic director at Indianapolis Motor Speedway).[226] Racing recordRacing career summary

American open-wheel racing(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position) USAC Championship Car

PPG Indy Car World Series

Indianapolis 500

NASCAR(key) (Bold – Pole position awarded by qualifying time. Italics – Pole position earned by points standings or practice time. * – Most laps led.) Grand National Series

Daytona 500

24 Hours of Le Mans results

Complete Formula One World Championship results(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position; races in italics indicate fastest lap)

Complete Formula One non-championship results(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position; races in italics indicate fastest lap)

Other race results

Autobiographies

See also

Notes and referencesNotes

References

Further reading

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Mario Andretti. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mario Andretti. Look up Mario Andretti in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||