|

Master of cardinal de BourbonThe Master of Cardinal de Bourbon was an anonymous master illuminator active in France between 1470 and 1500. His name was inspired by the manuscript evoking the life and miracles of Saint Louis, illuminated for the cardinal and archbishop of Lyon, Charles II de Bourbon. Little is known about his career, which is largely based on conjecture. Born in Flanders, he trained in the orbit of the Master of Margaret of York's group in the Bruges region. He may have passed through Rouen in the 1470s, before settling in Paris in the 1480s, where he illuminated a large number of manuscripts for relatives of King Louis XI. It has been suggested that he was identified with Guérard Louf, a painter and sculptor from Utrecht who settled in Rouen, but this identification has since been called into question. His style is marked by miniature frames imitating Gothic architecture, characters with strong physiques and expressive faces, a taste for detail, particularly in clothing, and a concern for realism, sometimes bloody, typical of Flemish book illumination of his time. He also used complex staging techniques, combining several perspectives in a single image and compartmentalizing the miniatures, all enhanced by shimmering colors. His style was inspired by both Dutch and Parisian illumination. However, his major works, such as La vie de saint Louis and the chronicle of the Siege of Rhodes, show his originality. In all, sixteen books of hours and ten other manuscripts are attributed to him in whole or in part. He may also have created models for engravings, panel paintings, and murals, but no work is attested as his own. Constitution of the corpus His style was studied in 1935 in a monograph devoted to one of his books of hours, the Un livre d'heures: manuscrit à l'usage de Mâcon, but no connection was made with his other works.[1] In 1982, American art historian John Plummer compiled a list of four of his works, including the Siraudin hours and a pontifical in the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. He then located his activity in Burgundy.[2] On the occasion of the publication of a work devoted to the Livre des faiz monseigneur saint Loys in 1990,[3] François Avril gave him a conventional name, the “Maître du Cardinal de Bourbon”, about Charles II de Bourbon, archbishop of Lyon and cardinal, who commissioned the work. The French historian located the work in Paris and added three other books of hours to the artist's list of works. He completed the corpus with two new manuscripts in 1993.[4] Finally, Isabelle Delaunay, in her thesis defended in 2000, further completed the corpus with the help of François Avril, and compared it with various engravings. She proposed its identification and location in Rouen.[5] In 2010, Yolande Fouquet-Réhault defended her thesis on the anonymous master, clarifying his style, influences, and commissioners.[6] In the 2015 art history thesis on the Parisian bookseller Antoine Vérard, Louis-Gabriel Bonicoli extended Delaunay's conclusions concerning the engravings associated with the Master or his workshop and proposed new attributions along these lines (the resulting corpus amounts to 868 matrices, produced between 1485 and 1497).[7] Biographical detailsFlemish originsThe style of the miniatures by the Maître du Cardinal de Bourbon has been compared to Flemish illumination of the 15th century, and more specifically to the style of the Master of Margaret of York. Many of the details in the Master's miniatures are reminiscent of elements specific to this artist or his collaborators, particularly the Master of the Jardin de Vertueuse Consolation or the Master of Fitzwilliam 268, whose motifs he copies. From the latter, he borrowed the drapery of Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross, taken directly from a book of hours for the use of Rouen in the collection of René Héron de Villefosse, and reproduced in the Le Clerc Hours and the David in prayer for the hours in the Tenschert bookshop.[8] Like them, he demonstrates a taste for detail and anecdote, as well as meticulous landscapes. All these elements seem to indicate that the master may have come from Bruges.[9] Venues and sponsors  Isabelle Delaunay hypothesizes that the artist came to France via Rouen in the 1470s.[8] At this time, ties between the capital of Normandy and Flanders were close, and Rouen's town councilors repeatedly called on artists from the north to decorate manuscripts. Louis, bâtard de Bourbon, lieutenant-general of Normandy and admiral of France, commissioned a manuscript on the life of Alexander, now in the Austrian National Library, in which Delaunay believed he could see the master's hand. There were also links between Flemish commissioners and artists based in the Normandy region. Louis de Gruuthuse, a prince and bibliophile from Bruges, commissioned illuminations in Rouen, in particular a miniature for a manuscript of the Livre des tournois. These attributions are not unanimous and several art historians have cast doubt on the artist's passage through Rouen.[10] More certain is the fact that the artist settled in Paris, a major artistic hub at the time, where customers from all over the northern half of France came to order books. Many artists from Flanders, and illuminators in particular, had settled here. In addition to the Master of Boucicaut and the Limbourg brothers in the early 15th century, André d'Ypres and his sons, key figures on the Parisian artistic scene in the Master's time, also came from the Netherlands. The Master of the Cardinal de Bourbon was probably in Paris in the 1480s, and incorporated elements typical of local illumination into his style, such as the cloisonné layout of the miniatures, as seen in Maître François. Several members of Louis XI's entourage commissioned manuscript illuminations from him: in addition to the aforementioned Louis bâtard de Bourbon, Antoine de Chourses, advisor and chamberlain to the king, commissioned at least three works from him, along with his wife Catherine de Coëtivy. Pierre Le Clerc, who probably commissioned the book of hours that bears his name, also holds the title of royal advisor. Charles II de Bourbon, the cardinal who gave his name to the anonymous master and commissioned the miniatures of a life of Saint Louis, was also an advisor and principal diplomatic negotiator. Finally, close to the sovereign was Pierre d'Aubusson, Grand Master of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem and commissioner of a chronicle of the siege of Rhodes. Not all these figures lived in Paris, but on several occasions, they commissioned works of art here.[11] Isabelle Delaunay suggests that the artist may have passed through Amiens around 1489-1490,[8] where he illuminated a book of hours and perhaps a pontifical for Pierre Versé, the city's bishop at the time. Isabelle also attributes to him the paintings for the tomb of Ferry de Beauvoir, then in the choir of Amiens Cathedral. However, this last hypothesis is not unanimous, as the master could just have moved to Amiens temporarily.[10] His identificationIsabelle Delaunay has put forward the hypothesis that the master could identify with an artist identified in the Rouen archives, a certain Guérard Louf or Gérard Loef, a painter and sculptor originally from Utrecht who arrived in the city no doubt to work on the Notre Dame Cathedral construction site. In 1465, the cathedral's chapter called on craftsmen from Flanders and the Netherlands, and according to a document dated 1472, Guérard Louf, resident in the capital between 1466 and 1475, founded a chapel in the cemetery of the city's Hôtel-Dieu hospital, where he set up a brotherhood of the deceased, made up of painters and sculptors from the north.[12] However, this identification is not unanimously accepted, as the sources seem to indicate that the artist settled permanently in Rouen, whereas the manuscripts attributed to him show that he left the city as early as 1480.[13] Furthermore, Caroline Blondeau's research into Rouen's artistic milieu in the second half of the 15th century has determined that Guérard Louf died shortly after 1478, which would invalidate Isabelle Delaunay's hypothesis.[14] Characteristics of his styleThe miniatures of the Maître du Cardinal de Bourbon can be distinguished from those of other artists of his time by several elements. He frequently used flamboyant Gothic architectural borders around his miniatures, as well as columns imitating marble, and reticulated ornamentation. In addition, he repeatedly inserts drawings into the frames, usually of statues representing figures with a symbolic link to the episode depicted, and occasionally adopts a frame imitating goldsmith's work, with precious stones and pearls. This use is reserved for miniatures depicting a subject that is to be given particular prominence in the work, as in the most important episodes of the Life of Saint Louis[15].

The composition of the miniatures helps determine his style: the architecture of the buildings compartmentalizes the scenes depicted. This process, invented by Maître François, is frequently found in several of his manuscripts, such as the Vie de saint Louis, the heures de Mâcon, and the Geste de Rhodes. He also sometimes isolated certain scenes using a décor, such as a rock in the shape of a sugar loaf, or even created complex stagings using a variety of perspectives, such as multiple vanishing lines in the same scene, parallel shots or, when necessary, close-ups and cutaways.[16]

The master depicts two characteristic types of figures: slender silhouettes, usually reserved for young people or the military, and rounder, better-proportioned silhouettes, reserved for ecclesiastics and writers. Their faces are often expressive but rarely individualized, as is still the case in contemporary illumination. He was able to paint truly realistic portraits of the most important figures, such as those who commissioned the manuscripts or their entourage. Such is the case of Cardinal de Bourbon and certain members of the assembly in the Vie de saint Louis, or Pierre d'Aubusson and his close advisors in the Geste de Rhodes. Other portraits can be individualized, for example a Virgin, an Amazon, or a bishop.[17]

The master's final characteristic is his preoccupation with realism and detail, found in the Flemish Primitives. He took particular care in depicting animals, musical instruments, various trades, and their tools. This realism is sometimes taken to extremes in violent scenes of war or murder, whether they concern the battles of Saint Louis or the siege of Rhodes. The same attention to detail is evident in the characters' clothing, particularly liturgical costumes, which makes it easy to distinguish the role of each individual. Hairstyles, too, are the object of special care. The colors of these miniatures are particularly rich, with gold used for relief and modeling, and alternating warm and cool colors. This practice contrasts sharply with the pale colors used in the Parisian illumination of the period. The use of colors is well mastered, and the painter applies them to the page in successive strokes, a technique that seems to indicate that he may have produced paintings as well as illuminations.[18]

ArtworkMajor artworksLivre des faiz Monseigneur saint LoysThe work is a compilation of episodes from the life of Louis IX and the miracles that took place at his tomb after his death, written by an anonymous author. It was commissioned by Charles II de Bourbon, cardinal and archbishop of Lyon around 1480-1482, who saw it as an opportunity to glorify his ancestor. The work was intended for one of the wives of his brother, Duke Jean II de Bourbon, who, according to the date of the manuscript and certain heraldic clues, could be Jeanne de France (1435-1482). This is the most ambitious work illuminated by the anonymous master who gave it its conventional name. It is large in format, on the model of the Grandes Chroniques de France, whereas other hagiographic books are usually smaller. All the chapters of the work are illuminated: the prologue (dedication miniature), the 41 chapters of the king's life (f.7-f.83), then the 75 miracles of the saint (f.84-115v), a chapter on his canonization, and a conclusion, for a total of 122 miniatures, 48 of which are full-page. Here, the master develops an original iconographic program while remaining very close to the text. According to François Avril, slight differences in certain miniatures suggest the intervention of a workshop.[19][20] Saint Louis is depicted in different ways according to his different roles, whether as monarch, husband, father, or Christ-like figure[21].

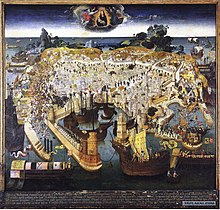

Gestorum Rhodie obsidionis commentariiDated 1483, this work by Guillaume Caoursin, vice-chancellor of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, recounts the siege of Rhodes three years earlier. It is a rare example of a chronicle evoking events contemporary with its writing, a veritable work of propaganda for the Order of Chivalry, designed to convince Western sovereigns to support their fight against the Turks. The work contains 51 full-page miniatures, 32 of which illustrate the siege itself, 4 the death of Mehmed II and 11 the story of Zizim. The manuscript was destined for the Order's Grand Master, Pierre d'Aubusson, with almost every miniature depicting him.[22][23] The draft of Caoursin's manuscript, still preserved in the Vatican Apostolic Library (Reg. Lat. 1847), contains part of the illuminator's instruction book. It details every monument, every character and every costume to be depicted in the work.[24] The author also indicates that he is sending a painting of the city of Rhodes to serve as a model. Eight miniatures are topographical views of the city, four of which are general aerial views, while the other four show details of the fortifications.[25]

Books of HoursFifteen books of hours have been attributed to him in whole or in part, and a sixteenth has recently been identified and acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The use of these books varies widely: Paris, Amiens, Mâcon, Angers, reflecting the very diverse origins of the commissioners. All have a base of identical iconographic motifs. However, two books stand out for their high quality of execution and the originality of their compositions: the hours of Mâcon and the hours of the Librairie Tenschert. The others were generally produced more quickly, and feature miniatures of very variable quality, suggesting the intervention of workshop collaborators.[26]

Religious, historical and moralizing booksOther manuscripts attributed to the Master include two liturgical manuscripts, three historical chronicles and two moralizing books. Three other works are simply collaborations in which the Master of Cardinal de Bourbon's contribution is occasional.[35]

Other proposals for the allocation of works The illuminations by the Master of Cardinal de Bourbon have been associated with other types of work. Indeed, illuminators of the late 15th century were often also painters and suppliers of cartoons for other media such as stained glass, tapestry or engraving, as was the case with the Master of Anne de Bretagne in Paris at the same period. Isabelle Delaunay has found the master's hand in many engravings, such as the woodcuts he may have designed for a book of hours printed by Antoine Caillaut in Paris in 1489, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Vélins 1643).[49] She also recognizes the master's hand in the paintings on the tomb of Ferry de Beauvoir in the choir of Amiens Cathedral, commissioned in 1489 by his nephew Adrien de Hénencourt, canon of the cathedral chapter.[50][51] All around the coffin in which the bishop's recumbent relies, angels and canons are depicted in trompe-l'œil, drawing a veil over the tomb and a representation of the coat of arms and the mystic lamb. The canon on the right recalls the figure of Saint Bernard in the Hours of Mâcon. The painting behind the recumbent bed depicts the apostles, reminiscent of those, or the Magi, from the same Hours. Some historians question this attribution.[52]  Finally, a painting on wood, now preserved in Épernay, depicting the siege of Rhodes, is sometimes attributed to the anonymous master. It was François Avril who first made the connection between this painting, possibly commissioned by Louis XI in the early 1480s for Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, and the manuscript of La Geste de Rhodes.[53] Indeed, four miniatures in the manuscript (folios 18, 32, 37v, 48v.) show the same general view of the siege of the island and the fortified city; moreover, the two works are characterized by very similar topographical precision and an almost identical Flemish-inspired treatment of the figures and atmospheric perspective. However, as Fouquet points out, it is difficult to identify with any certainty the hand of Cardinal de Bourbon's Master in this painting.[54] See alsoReferences

Bibliography

Information related to Master of cardinal de Bourbon |