|

Peter Lalor

Peter Fintan Lalor (/ˈlɔːlər/;[1] 5 February 1827 – 9 February 1889) was an Irish-Australian rebel and, later, politician, who rose to fame for his leading role in the Eureka Rebellion, an event identified with the "birth of democracy" in Australia. Early lifeLalor was born at Tenakill House, Raheen, in Queen's County (later Laois) in Ireland, which was part of the United Kingdom at the time. He was the son of Ann (née Dillon) and Patrick "Patt" Lalor, a landowner and supporter of the abolition of tithes, who was a member of the British parliament (MP) in 1832–1835. Patt Lalor was the first Catholic MP from Queen's County since the anti-Catholic Test Acts of the 17th century. He had 11 children: Joseph Lalor, James Fintan Lalor, Richard Lalor, Mary Lalor, Patrick Lalor, Thomas Lalor, Catherine Lalor, Margrett Ellen Lalor, Jerome Lalor, John Lalor and William A. Lalor Sr., of whom Peter was the youngest. The eldest brother was James Fintan Lalor, who was later involved in the Young Ireland movement and the unsuccessful Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. Another brother, Richard Lalor, also became a member of the British Parliament, representing the Parnellite nationalist party. Their mother died on 4 June 1835 and Patt Lalor later remarried, to Ellen Mary Anne Loughnan, with whom he had no children. Peter Lalor was educated at Carlow College and trained as a civil engineer at Trinity College.[2] Three of the Lalor brothers migrated to America and fought on both sides of the Civil War. However, Peter and his brother Richard decided to go to Australia, arriving in Victoria in October 1852. Lalor worked briefly on the construction of the Geelong to Melbourne railway, but resigned to take part in the Victorian Gold Rush. He began mining in the Ovens diggings (Beechworth), then moved to the Eureka Lead at Ballarat where he befriended Duncan Gillies, who later became Premier of Victoria. His brother Richard returned to Ireland, becoming politically active and a member of the House of Commons.[3] Events leading to the Eureka StockadeAgitation against the requirement to buy a monthly licence to mine for gold began with the Red Ribbon Movement at Bendigo in 1853, and was quickly taken up at Ballarat. A Reform League was formed amongst the diggers on the various goldfields for the redress of grievances. Provocatively, in October 1854, the Government ordered the police to go out hunting for unlicensed diggers two times a week. In the later half of 1854, a digger named James Scobie was killed in a scuffle at the Eureka Hotel, on Specimen Hill. James Bentley, the hotel publican, was considered by the diggers to have participated in the murder. He and others were charged with murder and arrested, but were discharged after a trial that miners believed was corrupt.[4] An indignation meeting was held at Ballarat on 17 October, close to the spot where Scobie had been killed. At the meeting, a committee was appointed, which included Peter Lalor, to raise money for the further prosecution of Bentley. The goldfield authorities, fearing that the meeting might lead to an attack on Bentley's hotel, sent police to guard it. A youth threw a stone at the lamp in front of the building, breaking the glass. That sparked cries of "Down with the house" and "Burn it", and the angry mob stormed the hotel and set it on fire. Three people were arrested and charged with acts of incendiarism, tried, and imprisoned. A mass meeting was held on Bakery Hill on 11 November 1854, to demand the release of the alleged incendiaries. It also passed resolutions affirming the right of the people to parliamentary representation, demanding manhood suffrage, the abolition of property qualification for members of parliament, the payment of members, short parliaments (the gap between elections), and the abolition of the Gold Commission and diggers' licenses. Bentley, in the meantime, had been re-arrested, on the advice of the Attorney-General William Stawell, for the murder of Scobie. He was convicted and sentenced to three years working on the roads. On 29 November, a meeting of about 12,000 people was held at Ballarat. It is said to be the first public meeting that Lalor addressed, and he moved one of the resolutions which was passed. It called for a meeting of the Reform League for the following Sunday to elect a central committee. An "insurgent flag" was hoisted on the platform, which consisted of a representation of the Southern Cross constellation on a dark blue background. Another resolution passed at the meeting declared the miner's license fee to be an unjustifiable imposition. A bonfire was soon kindled and many licences were burnt. At this meeting, the rebellion was formally inaugurated.[4] Eureka Stockade

The Eureka Oath from Lalor's famous speech in 1854.

Lalor led the miners' opposition against the incompetent and often brutal administration of the goldfields authorities, and was elected to lead the men in the armed uprising after the meeting on Bakery Hill. The diggers erected a protective stockade, which was overrun by troops and police on the morning of 3 December. Lalor was seriously wounded in the left arm, resulting in its amputation. A warrant for his arrest on charges of sedition was issued, but he was taken from Ballarat by his supporters and hid in the Young Queen Hotel in South Geelong. The warrant was withdrawn in June 1855 after juries had found 13 other ringleaders not guilty of sedition. As a result of the uprising, a number of the miners' complaints were resolved. Legislation was passed to give miners the right to vote. A new form of licensing was introduced: a miner's right, costing £1 per year. The monthly gold tax was abolished. A general amnesty for the three miners arrested after the Bentley's Eureka Hotel fire and the 114 arrested at the Eureka Stockade was proclaimed. Lalor's escape

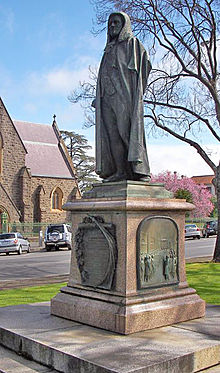

Politics Due to the political changes caused by the Eureka Stockade, Lalor was elected to the Victorian Legislative Council in November 1855 as one of the two members for the new district of Ballaarat,[6] and remained in that role until March 1856.[7][8] At the general election in September and October 1856, under the new, more democratic constitution, which featured near-universal white male suffrage, Lalor was elected unopposed to the Legislative Assembly seat of North Grenville (Ballarat West). Because he was the Eureka hero, his policies were not scrutinised at all before the election and his later voting record as a parliamentarian shows he opposed a bill to introduce full white male suffrage in the colony of Victoria.[7][8] During a speech in the Legislative Council in 1856 he said, "I would ask these gentlemen what they mean by the term 'democracy'. Do they mean Chartism or Communism or Republicanism? If so, I never was, I am not now, nor do I ever intend to be a democrat. But if a democrat means opposition to a tyrannical press, a tyrannical people, or a tyrannical government, then I have been, I am still, and will ever remain a democrat."[9] Historian Weston Bate wrote that the role of landowner and company director seemed to suit Lalor more than that of rebel, and that he "disgraced himself in democratic eyes" by trying to use Chinese as strike-breakers at the Clunes mine, of which he was a director. Some argue that he was ruthless in using low-paid Chinese workers to get rid of Australians seeking better and safer working conditions. In parliament, he supported a repressive land Bill in 1857 which favoured the rich, and there were 17,745 Ballarat signatures to a petition against Lalor's land Bill.[10] Withers and others were puzzled and hurt that the folk hero should prove to be a better fighter for money and political position than for the people's rights. Like many young radicals, he undoubtedly became more conservative in later life. However, he was consistent in being a risk-taker and, in his later business career, undoubtedly suffered lows as well as highs, at one point narrowly avoiding having to declare bankruptcy.[11] Lalor held North Grenville until it was abolished in 1859, and never represented Ballarat again. In the October 1859 election, he stood for and won South Grant in the Legislative Assembly.[7]  Lalor held South Grant for over eleven years, until the general election in 1871. At that election, he unsuccessfully contested the seat of North Melbourne.[7] In the 1874 general election, he was elected in South Grant once again. At the 1877 election, he successfully contested the Legislative Assembly seat of Grant, which he held for almost twelve years, until his death in February 1889.[7] Lalor's key ministerial postings were as Commissioner of Trade and Customs and Postmaster-General of Victoria from August to October 1875, then Commissioner of Trade and Customs from May 1877 until March 1880, as well as Postmaster-General again from May to July 1877. Lalor also served as chairman of committees in the period from 1859 to 1868.[7] As the successor to Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, his most effective political post was probably that of Speaker, a position he held from 1880 until 1887, when illness forced his retirement, after which he was awarded a pension of £4,000 by parliament. Later life and death Lalor married Alicia Dunne on 10 July 1855 in Geelong. Their daughter, Anne (Annie), was born in Prahran in 1856, and their son, Joseph, was born at Sandridge (now called Port Melbourne) on 18 December 1857. Annie Lalor married Thomas Lempriere in 1882, but died three years later of pulmonary phthisis. Joseph Lalor became a medical doctor, marrying Agnes McCormick of Dublin, Ireland and leaving descendants. Alicia Lalor died on 17 May 1887 at the age of 55 years. Following her death, Peter Lalor took leave from Parliament and visited San Francisco, California. Lalor died on Saturday, 9 February 1889 at age 62, four days after his birthday, at his son's home in Richmond, and was buried at the Melbourne General Cemetery.[12] Legacy A statue of Peter Lalor was erected at Sturt Street in Ballarat in 1893. It was presented to the municipality by a friend of Lalor's, James Oddie, who was also first chairman of the city, and was unveiled by another friend, the Premier, the Hon Duncan Gillies. The Melbourne suburb of Lalor, Victoria, was named after him in 1945. The suburb was originally pronounced "LAW-luh", after Peter Lalor, and although many people still pronounce it as such, in recent times the pronunciation "LAY-lor" has become predominant. Peter Lalor Vocational College (formerly Peter Lalor Secondary College), in the Lalor area, is named in his honour. A federal electorate in the south-western suburbs of Melbourne, the Division of Lalor, was named after him in 1948. It has been held successively by senior Labor figures Reg Pollard, Jim Cairns, Barry Jones and Julia Gillard. The suburb of Lalor is not in the electorate, which is pronounced "LAW-luh". Lalor Street in Ballarat East was also named in his honour. The University of Ballarat (now known as Federation University Australia) honoured Lalor by naming one of the two Halls of Residence at he Mt Helen campus after him (the other being named after Bella Guerin, the first woman to graduate from an Australian university). Portrayals of Lalor's role in the Eureka Rebellion appear in film. For further information about the various films depicting Peter Lalor, see: Eureka Rebellion in popular culture. Since 1992, Lalor has been depicted in the commemorative Son et lumière "Blood Under the Southern Cross" at Sovereign Hill.[18] A caricature bollard by artist Jan Mitchell, depicting Peter Lalor holding the Eureka flag, was erected on the Geelong foreshore in 1999 as part of the Waterfront Geelong bollard walk. His portrait is featured on two commemorative postage stamps, a 38c Irish stamp released on 3 May 2001 in the "Rebel Spirit, Irish Heritage of Australia" series, and a 2004 AUD2.45 Australian stamp commemorating the Eureka Stockade.[19] References

Further reading

Additional sources listed by the Australian Dictionary of Biography:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||