|

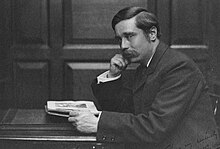

Political views of H. G. Wells H. G. Wells (1866–1946) was a prolific English writer in many genres, including the novel, history, politics, and social commentary, and textbooks and rules for war games. Wells called his political views socialist. The Fabian SocietyWells was for a time a member of the Fabian Society, a socialist organization, but broke with them as his creative political imagination, matching the originality shown in his fiction, outran theirs.[1] He later grew staunchly critical of them as having a poor understanding of economics and educational reform, but remained committed to socialist ideals. He ran as a Labour Party candidate for London University in the 1922 and 1923 general elections after the death of his friend W. H. R. Rivers, but at that point his faith in the party was weak or uncertain.[citation needed] ClassSocial class was a theme in Wells's The Time Machine in which the Time Traveller speaks of the future world, with its two races, as having evolved from

Wells has this very same Time Traveller, reflecting his own socialist leanings, refer in a tongue-in-cheek manner to an imagined world of stark class division as "perfect" and with no social problem unsolved. His Time Traveller thus highlights how strict class division leads to the eventual downfall of the human race:

In his book The Way the World is Going, Wells called for a non-Bolshevik form of socialism to be set up that would avoid conflict between nations.[3] DemocracyFred Siegel of the center-right Manhattan Institute wrote of Wells's unflattering take on American democracy: "Wells was appalled by the decentralised nature of America's locally oriented party and country-courthouse politics. He was aghast at the flamboyantly corrupt political machines of the big cities, unchecked by a gentry that might uphold civilised standards. He thought American democracy went too far in providing leeway to the poltroons who ran the political machines and the 'fools' who supported them."[4] Siegel goes on to note Wells's dislike of America's not allowing African Americans to vote.[4] World governmentHis most consistent political ideal was the world state. He stated in his autobiography that from 1900 onward he considered a World State inevitable. He envisioned the state to be a planned society that would advance science, end nationalism, and allow people to progress by merit rather than birth. Wells's 1928 book The Open Conspiracy argued that groups of campaigners should begin advocating for a "world commonwealth", governed by a scientific elite, that would work to eliminate problems such as poverty and warfare.[5] In 1932, he told Young Liberals at the University of Oxford that progressive leaders must become liberal fascists or enlightened Nazis who would "compete in their enthusiasm and self-sacrifice" against the advocates of dictatorship.[6][7] In 1940, Wells published a book called The New World Order that outlined his plan as to how a World Government would be set up. In The New World Order, Wells admitted that the establishment of such a government could take a long time, and be created in a piecemeal fashion.[8] EugenicsSome of Wells's early science fiction works reflect his thoughts about the degeneration of humanity.[9] Wells doubted whether human knowledge had advanced sufficiently for eugenics to be successful. In 1904, he discussed a survey paper by Francis Galton, co-founder of eugenics, saying, "I believe that now and always the conscious selection of the best for reproduction will be impossible; that to propose it is to display a fundamental misunderstanding of what individuality implies... It is in the sterilisation of failure, and not in the selection of successes for breeding, that the possibility of an improvement of the human stock lies". In his 1940 book The Rights of Man: Or What are we fighting for? Wells included among the human rights he believed should be available to all people, "a prohibition on mutilation, sterilization, torture, and any bodily punishment".[10] RaceIn 1901, Wells wrote Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought, which included the following views:

Wells's 1906 book The Future in America, contains a chapter, "The Tragedy of Colour", which discusses the problems facing African Americans.[12] While writing the book, Wells met with Booker T. Washington, who provided him with much of his information for "The Tragedy of Colour".[13] Wells praised the "heroic" resolve of African Americans, stating he doubted if the US could:

In his 1916 book What is Coming?, Wells states, "I hate and despise a shrewish suspicion of foreigners and foreign ways; a man who can look me in the face, laugh with me, speak truth and deal fairly, is my brother, though his skin is as black as ink or as yellow as an evening primrose".[14] In The Outline of History, Wells argued against the idea of "racial purity", stating: "Mankind from the point of view of a biologist is an animal species in a state of arrested differentiation and possible admixture . . . [A]ll races are more or less mixed.".[15] In 1931, Wells was one of several signatories to a letter in Britain (along with 33 British MPs) protesting against the death sentence passed upon the African American Scottsboro Boys.[16] In 1943, Wells wrote an article for the Evening Standard, "What A Zulu thinks of the English", prompted by receiving a letter from a Zulu soldier, Lance Corporal Aaron Hlope.[17][18][19] "What a Zulu thinks of the English" was a strong attack on anti-black discrimination in South Africa. Wells claimed he had "the utmost contempt and indignation for the unfairness of the handicaps put upon men of colour". Wells also denounced the South African government as a "petty white tyranny".[17][18][19]

First World WarHe supported Britain in the First World War,[24] despite his many criticisms of British policy, and opposed, in 1916, moves for an early peace.[25] In an essay published that year he acknowledged that he could not understand those British pacifists who were reconciled to "handing over great blocks of the black and coloured races to the [German Empire] to exploit and experiment upon" and that the extent of his own pacifism depended in the first instance upon an armed peace, with "England keep[ing] to England and Germany to Germany". State boundaries would be established according to natural ethnic affinities, rather than by planners in distant imperial capitals, and overseen by his envisaged world alliance of states.[26] In his book In the Fourth Year published in 1918 he suggested how each nation of the world would elect, "upon democratic lines" by proportional representation, an electoral college in the manner of the United States of America, in turn to select its delegate to the proposed League of Nations.[27] This international body he contrasted with imperialism, not only the imperialism of Germany, against which the war was being fought, but also the imperialism, which he considered more benign, of Britain and France.[28] His values and political thinking came under increasing criticism from the 1920s and afterwards.[29] Soviet UnionThe leadership of Joseph Stalin led to a change in his view of the Soviet Union even though his initial impression of Stalin himself was mixed. He disliked what he saw as a narrow orthodoxy and intransigence in Stalin. He did give him some praise saying in an article in the left-leaning New Statesman magazine, "I have never met a man more fair, candid, and honest" and making it clear that he felt the "sinister" image of Stalin was unfair or false. Nevertheless he judged Stalin's rule to be far too rigid, restrictive of independent thought, and blinkered to lead toward the cosmopolis he hoped for.[30] In the course of his visit to the Soviet Union in 1934, he debated the merits of reformist socialism over Marxism-Leninism with Stalin.[31] MonarchyWells was a republican[32] and an advocate for the creation of republican clubs in the UK.[33] In 1914, Wells referred to the United Kingdom as a crowned republic.[34] Other endeavoursWells brought his interest in Art & Design and politics together when he and other notables signed a memorandum to the Permanent Secretaries of the Board of Trade, among others. The November 1914 memorandum expressed the signatories concerns about British industrial design in the face of foreign competition. The suggestions were accepted, leading to the foundation of the Design and Industries Association.[35] In the 1920s he was an enthusiastic supporter of rejuvenation attempts by Eugen Steinach and others. He was a patient of Dr Norman Haire (perhaps a rejuvenated one) and in response to Haire's 1924 book Rejuvenation: the Work of Steinach, Voronoff, and others,[36] Wells prophesied a more mature, graver society with 'active and hopeful children' and adults 'full of years' where none will be 'aged'.[37] In his later political writing, Wells incorporated into his discussions of the World State a notion of universal human rights that would protect and guarantee the freedom of the individual. His 1940 publication The Rights of Man laid the groundwork for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[38] SummaryIn the end Wells's contemporary political impact was limited, excluding his fiction's positivist stance on the leaps that could be made by physics towards world peace. His efforts regarding the League of Nations became a disappointment as the organization turned out to be a weak one unable to prevent the Second World War, which itself occurred towards the very end of his life and only increased the pessimistic side of his nature. In his last book Mind at the End of its Tether (1945) he considered the idea that humanity being replaced by another species might not be a bad idea. He also came to refer to the Second World War era as "The Age of Frustration". References

|