|

Timbuctoo, New Jersey

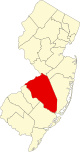

Timbuctoo is an unincorporated community in Westampton Township, Burlington County, New Jersey.[2] Located along the Rancocas Creek, Timbuctoo was settled by formerly enslaved and free Black people, beginning in 1826.[3] It includes present day Church Street, Blue Jay Hill Road, and adjacent areas. At its peak in the mid-nineteenth century, Timbuctoo had more than 125 residents, a school, an AME Zion Church, and a cemetery. The key remaining evidence of this community is the cemetery on Church Street, which was formerly the site of Zion Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal African Church. Some current residents are descendants of early settlers.[4][5][6] History Timbuctoo was founded by free Blacks and former slaves in 1826, in a region of New Jersey where the influence of Quakers was strong.[7][8] Timbuctoo appeared on Burlington County maps as early 1849,[9] and continues to appear on maps today.[10] A review of deeds in the Burlington County Clerk’s office found that the first sales of land to Black people in the area that would later be named Timbuctoo occurred in September of 1826, when Wardell Parker,[11] Ezekiel Parker,[12] David Parker[13] and Hezekiah Hall[14] purchased parcels of land from a Quaker farmer named William Hilyard. The parcels ranged from one-half acre to one-and-a-half acres in area, costing between $8.33 to $24.05. In 1829, another Quaker farmer named Samuel Atkinson sold land to Black people, beginning with one acre to John Bruer in 1829 for $30,[15] one-half acre to Major Mitchell in 1830 for $15,[16] and one-and-one-fifth acre to Peter Quire in 1831 for $36.[17] The deed to Major Mitchell was the first to use the name Timbuctoo. By 1845, Timbuctoo consisted of twenty-four lots covering approximately fifteen acres. In 1834, Peter Quire and his wife Maria subdivided their lot to provide a location for the African Union School.[18] Astle and Weston point out the school’s deed makes a strong statement about the early settlers’ autonomy and intent on self-determination.[19] After describing the buyers and sellers and a legal description of the property, it says: Whereas, in the Settlement of Tombuctoo . . . and in the vicinity thereof, there are many People of Colour (so called), who seem sensible of the advantages of a suitable school education and are destitute for a house for that purpose. And the said Peter Quire, and Maria, his wife in consideration of the premises, and the affection they bear to the people of Colour, and the desire they have, to promote their true and best interests, are minded to settle, give, grant and convey . . . said premises to the uses and intents hereinafter pointed out and described. This deed also identifies the school’s trustees and stipulates that future trustees must be “people of colour who live within ten miles of the premises,” plainly indicating the settlers’ intent to be in charge of education in their community. Perhaps more clearly than any other extant documentation on Timbuctoo’s early history, this deed indicates the settlers had the agency to establish institutions on their own terms, and describe rules of operation that preserved Black leadership, with some degree of deference by the White majority. Recording deeds in the county clerk’s office in this era meant a county official would hand-write a second copy for the official record. Therefore, every detail of content would be known to the local government. The 1854 deed for the Zion Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal African Church[20] also identifies trustees and a governance structure, describing affiliation with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AME Zion) Church, which is a national denomination established in New York City in 1821 that remains in existence today. This deed indicates the premises would also be used for a cemetery: “a place for the burial of the dead of such as are in connection with said church or the descendants thereof, (and such others as the majority of the Trustees for the time being may permit) forever.” From this we conclude that a majority of as many as one hundred fifty unmarked graves identified by ground penetrating radar (GPR) in 2009 are most likely members or affiliates of this church that operated through approximately 1915.[21] The predominance of US Colored Troops (USCT) gravestones in the cemetery today (eight out of eleven), resulted in the cemetery being formally designated as a Civil War cemetery in 2006.[21] However, the number of USCT gravestones can be attributed to the fact that the troops received stone grave markers as a benefit of military service. By contrast, wooden grave markers were common for ordinary citizens during that time period; these would not survive time. Interpretive signage installed in the cemetery in 2018 clarifies the cemetery’s history. By 1860, the population of Timbuctoo had grown to about 125.[22] As illustrated in the adjacent parcel map, this area comprised approximately 15 acres. The US Census identified the "Village of Timbuctoo" as a separate entity within Westampton Township for the first time in 1880,[23] enumerating 108 residents and 29 households. David Parker, who was one of the original 1826 settlers, emerged as leader of the community, and remained in this position for most of his life. Parker was associated with multiple land transactions and had served as a founder and trustee of the Zion Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal African Church referenced above. He was also a trustee and founder of the Beneficial Society of the United Sons and Daughters of Timbuctoo and Vicinity,[24] which was a benevolent society. Parker was often referred to as King David, both in the local newspaper, the New Jersey Mirror, and in major publications like the Philadelphia Inquirer, and the Camden Post.[19] Clearly, it was far more than a casual nickname. His 1877 obituary[25] in the New Jersey Mirror begins as follows: “The King” Hath Departed.—“David Parker, an aged colored man who for perhaps a half a century has occupied a prominent position with his race in this vicinity, and who has commanded the respect and esteem of a large number of white friends, died at his residence in Timbuctoo on Sunday [June 24, 1877]… ‘King David’, as he had been known in other years, was possessed of more than ordinary intelligence and a determined will, which made him a natural leader among his people…and he was generally at the head of any movement among them… Original settler Hezekiah Hall also had a substantial obituary[26] in 1851 in the New Jersey Mirror, which says he had been enslaved by Charles Carroll of Carrollton, (a signer of the Declaration of Independence), and that “he was a man of unblemished character and his truly upright walk and Christian deportment commanded the highest respect.” Similarly, Lambert Giles, son-in-law of early settler John Bruer, had a flattering 1875 obituary[27] that says he was “regarded as about perfect in his art” (house painting), and that he would be “more missed than many of our more pretentious citizens.” In 1860, the Battle of Pine Swamp took place near Timbuctoo, when armed residents fought off an infamous "slave catcher," named George Alberti, who sought to capture Timbuctoo neighbor Perry Simmons and return him to enslavement in Maryland. David Parker led "the Timbuctoo warriors" in their victorious defense of Simmons, according to the New Jersey Mirror’s 1100-word account,[28] which includes numerous humorous anecdotes in criticism of the would be captors. Most notably, it says the “slave catchers” “left the scene of their brilliant achievement as if old Satan was after them.” During the postbellum period through the early twentieth century, the population of Timbuctoo declined. Beginning in the 1920s, a population influx attributed to the Great Migration increased the population. Today, many Timbuctoo descendants trace their ancestry in the community to the early decades of the twentieth century. There are four known families that descend from settlers that came to Timbuctoo before the Civil War. Three still own property and/or live in Timbuctoo. Resurgence of Timbuctoo's historic significanceThroughout most of the twentieth century, Timbuctoo was known locally "the Black section of town," without any recognition of any remarkable history, In 2009, officials from Temple University and the National Park Service met with Westampton Township Mayor Sidney Camp to inform him of Timbuctoo’s historic significance and to propose archaeological research. With funding from Westampton Township, and including subsequent leadership of Mayor Carolyn Chang, two field seasons of archaeological research ensued, ultimately identifying more than 15,000 artifacts,[29] some of which are on exhibition at the Burlington County Lyceum of History and Natural Sciences and the Rancocas Nature Center, as of January 2025. Principal Investigator Christopher Barton’s Temple University doctoral dissertation chronicled and interpreted the research findings of the excavations. These were published in a book entitled The Archaeology of Race and Class at Timbuctoo: A Black Community in New Jersey.[29] Using a community archaeology perspective, Barton “explores the intersectionality of life at Timbuctoo and the ways Black residents resisted the marginalizing structures of race and class.” Substantial publicity resulted from the archaeological investigations, including front page coverage in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the New York Times, and the Washington Post. The During this period, the Timbuctoo Advisory Committee, formed by Westampton Township’s governing body, conducted outreach and educational events, as well as installing signage to identify the community and educate area residents about the historical significance of Timbuctoo. In 2019, Guy Weston, a fifth great grandchild of 1829 Timbuctoo settler John Bruer, established the Timbuctoo Historical Society to coordinate Timbuctoo preservation educational efforts.[30] The society obtained ownership of the Timbuctoo cemetery in 2021. The society receives state and county funding for various preservation and educational initiatives, including a curriculum project in partnership with the Rancocas Valley High School district and the Westampton district, as well as a children’s book about Timbuctoo. In 2024, the society successfully prepared applications to have Timbuctoo listed on the New Jersey Black Heritage Trail and the National Park Service Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. As of January 2025, Weston has written or co-written fourteen scholarly or feature articles on Timbuctoo and related topics.[31] Weston says Timbuctoo and other antebellum free Black communities represent an underappreciated perspective in American history. “Free Black people were only 12% of the US Black population at the onset of the Civil War, but we were the vast majority in Northern states. We certainly had our struggles, but we also owned land, established institutions, and forged our own path. That needs to be part of the story too.” See alsoReferences

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||